One of the difficulties of writing a blog on African energy transition is the sheer variety of challenges across the continent. From South Africa’s task of moving away from near-total dependence on coal[1], to some countries producing too much power which they cannot absorb into the grids, to overall population growth, to the effects of COVID, to climate change, to ensuring that transition is socially just, they all make a mind-boggling mind-map!

Clarification

What is energy transition?

The International Renewable Energy Agency defines transition as;

“a pathway toward transformation of the global energy sector from fossil-based to zero-carbon by the second half of this century.”

Simple to say, but complex in detail, and nowhere more so than in Africa.

Energy transition involves providing as much power as possible for your country from renewable sources such as wind, solar, biomass, hydro-electric power and hopefully in the future, hydrogen[2]. It also entails developing and bringing online entire new suites of renewable energy technologies, modernising recycling, driving down the volume of single-use plastics and building a circular economy.

Given that energy is an economy (because nothing in an economy can happen without it), energy transition actually means transition of an economy. It is not as simple as switching from one set of power sources to another.

National grids and power infrastructure have to be re-configured and outlets provided to every residence whether on or off-grid;

Industrial processes and transport must be re-built to run on new fuels;

Power-purchase and consumer tariffs set which work for everyone from government down to the individual customers. There is little point in providing lots of power if no-one can afford to buy it;[3]

Regulation needs to be over-written in its entirety;

The symbiotic relationship

The symbiotic relationship

Agriculture needs to be thoroughly modernised, particularly bearing in mind the symbiotic African relationship between water, food, energy and health[4];

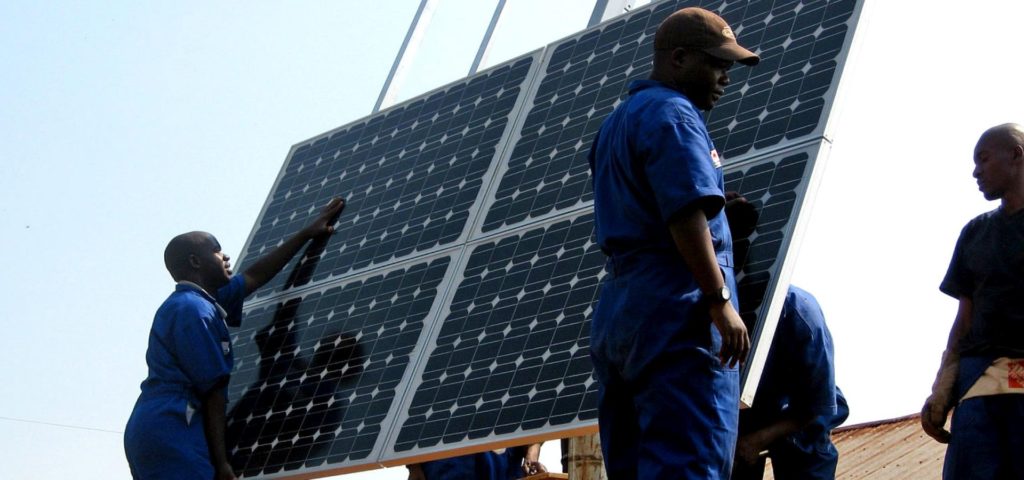

The vast array of skills necessary for a zero-carbon future have to be identified, taught via apprenticeships, vocational training and higher education, embedded into society, updated and deployed;[5]

Existing power industries must be managed out without leaving communities or whole countries high and dry.

And all of this needs to be done whilst maintaining basic governance and public services, not to mention managing the effects of COVID.

But all countries and continents are facing this challenge – why is Africa different?

African Population Projections 2015-2100.png

First, population. Currently 1.2bn, of whom approximately 60% have access to electricity, the continent’s inhabitants are scheduled to increase to 2.4bn by 2050, and a staggering 4bn by 2100.[6] Unlike Europe and the Americas with their largely static populations, to allow universal access to power by 2100 Africa must increase its current output by something like 500%, at the same time as fundamentally changing its nature (from fossil-based to renewables). China faces a similar, albeit smaller, moving target, but is better placed to execute the sweeping changes necessary due to being both homogenous (as opposed to 54 nations), and authoritarian.

Second, vulnerability to climate change. North Africa carries the highest levels of threat from climate change in the world. In addition to reducing rainfall and groundwater, and more frequent severe weather events, desertification marches inexorably northwards, whilst rising sea levels threaten large areas of developed and densely populated coastal territory.[7] In Alexandria, Egypt’s second largest city, about a quarter of the coast could be inundated if sea levels continue to rise, according to recent studies.[8] Can you imagine re-building a city’s power provision whilst also either moving a quarter of it out of harm’s way, or protecting it from the sea? Therefore the transition of African energy, and the associated transformation of their economies must be future-proofed against climate change.[9]

Third, natural resources, which in the case of Africa, contain two glaring paradoxes:

Given that the world currently relies on fossil fuels for 84% of power requirements, and that power requirements will rise sharply this century due to expanding population, fossil fuels will paradoxically be a large and critical part of the world’s energy mix until at least 2100 – renewables simply cannot grow fast enough to completely take over from oil and gas in that timeframe. So the world will need fossil fuels for most of this century, in order to survive whilst transitioning to renewables;

Perhaps a lesser known fact is that 23 minerals have been identified as crucial to global energy transition[10]. The largest deposits of these minerals are, yes, you guessed it, in Africa. So renewable energy needs functioning and, hopefully, clean mineral extractive industries.

Many of these resources are in Africa. 30% of global oil and gas discoveries from 2010 – 2014 were in sub-Saharan Africa, 40% of natural gas reserves found in the last decade have been in Africa (principally Tanzania and Mozambique)[11] and the region is scheduled to surpass Russia as the world’s leading gas supplier by 2040.[12]

And fourth, multiple sovereignties. Africa consists of 54 countries and its natural resources transcend boundaries. Egypt and Ethiopia are already at loggerheads because the filling of the Great Renaissance Dam started ahead of any agreement between the two countries and Sudan.[13] Persuading multiple countries to work together for the common good is a monumental task, although the continent’s excellent and coordinated response to COVID may offer both the template and the impetus to achieve this.

The backdrop to this debate is the existing challenges that Africa routinely faces; crime, extortion, migration and refugees, narcotics and terrorism[14], most of which are finding themselves with unaccustomed freedoms due the pandemic (my previous blog explores this).

So what?

Energy transition therefore actually means the transition of entire economies, Africa included. The transitions will need to provide a reliable, affordable, clean energy provision which works for consumers, providers, communities, countries and the continent, whilst the goalposts are moving because of the increasing population, at the same time as mitigating/surviving the worst effects of climate change, handling “normal” disruptions such as terrorism, cleaning up an expanding extractive industry with measures like Carbon Capture, Usage and Storage, revolutionising agriculture, managing the COVID fall-out and supporting other countries’ transitions with resources.

Wow…

My conclusion is that in this most testing of times, the principles of resilience at all levels, including national and supra-national, become ever more important:

All levels must scan the horizon. We know that terrorism is on the rise because of the commitment of security forces to COVID[15]. We know that water is running out in the Middle East and North Africa, and that sea levels are rising[16]. We know that the population is growing. We know that more hydrocarbon energy will be required before renewables can take over (if ever). We know that to power countries with renewables will take significant re-builds of grids, infrastructure and industries. So with all these challenges clearly visible in the not-too-distant future, the transition of economies must be meticulously analysed and planned, and thereafter future-proofed.

The transitions must work at all levels. Renewables, and the new jobs that come with them must be available in all areas and not just the big cities, to the energy entrepreneurs, to the small businesses of less than 20 employees (where most job creation happens in Africa[17]) and to the informal as well as the formal economies. It is just as important to replace the kerosene, candles and flashlights which remain prevalent throughout the rural areas in much of the continent as it is to install green urban streetlighting and internet access.

Crisis management and emergency response need to be re-examined and validated at all levels. The environment in which everyone lives and operates today is changing more quickly than we have seen in our lifetimes, and with Mother Nature having pressed a large re-set button in 2020, it is not safe to assume that the plans of 2019 will still work in 2021 onwards.

What are Africa currently doing well? A great deal is the answer, and here are some examples:

Through grid extensions and Liquid Petroleum Gas distribution networks, North Africa has achieved near-universal access to electricity and clean cooking (United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 7.1, heavily referenced in the African Union Agenda 2063), with approximately 20 million people gaining access since 2000, and the fastest improvements in rural areas. This makes the region an excellent example of global best practice.[18]

Taiba Ndiaye wind farm project, Senegal

In Senegal, President Macky Sall’s target of 20% of power coming from renewables was met in 2017, and by 2018 60% of the population had reliable access to electricity. Funded by oil and gas exports (there’s that paradox again), power transmission and distribution infrastructure was aggressively upgraded, and when the 46 turbines of the 158MW Taiba Ndiaye Wind Project come on stream they are predicted to push the national percentage of renewable power up to 30%.[19]

In Ghana, where there is a traditionally fragile grid which cannot always take the power produced and difficult “take or pay” financial arrangements[20], the Nzema Solar Power station will increase national electricity supply by 6%.[21]

Morocco, giving a lead to Africa as it does in many areas, is seeking to deploy 1.5GW of solar and wind and increase its percentage of renewable power provision to 52% by 2030 (in 2009 the country relied on hydrocarbon fuels for 90% of provision).[22]

Cape Verde’s Renewable Energy and Industrial Maintenance Centre (CERMI) teaches the design, assembly and maintenance of photovoltaic installations.[23]

The African Development Bank (AfDB) recently hosted a dialogue on building a Harmonised and Centralised Energy Database Through the Africa Energy Information System (AEIS). Attended by, among others, Amani Abou-Zeid, Commissioner for Infrastructure and Energy at the African Union Commission, the dialogue focused on digitalising the existing database to better appreciate the energy needs of multiple nations.

A stronger AEIS will raise the profile of energy statistics across Africa, with benefits for the countries themselves, as well as for the IEA and the global community of energy data producers and data users.

IEA and global energy statistics network (interEnerStat) will benefit from AFREC’s convening power and knowledge on national energy information systems.

AEIS will depend upon countries reinforcing their capacity to collect all the data needed – a progress beneficial to all data users.[24]

How can energy companies support African nations?

In short, they can transform themselves quickly and efficiently. Those that fail to do so are likely to be out of business shortly anyway.

As countries transition their energy industries and thereby their entire economies, with which many are already well-advanced, the energy companies operating there need to transform, and play their part in the recovery from the COVID period. If the energy transition, both on and off-grid, is not accelerated from its current pace, the recovery from the pandemic will be delayed.[25]

Firstly, understand how quickly and dramatically the energy sector is changing, and adapt to stay in business for the long term;

Work out what you are, what you can be, why you exist, and what makes you distinctive.

Be prepared to examine changing everything.

Improve discipline in finance, capital allocation, risk management, governance.

Broaden the portfolio to include renewables – this is where the investment is. Gain more investment, stay in business, and continue to provide energy to the host country.

Reduce debt (the traditional life-blood of Oil and Gas), and revisit business models if appropriate because demand, prices and investment are all highly volatile.

Secondly, stay safe;

Figure out how to operate safely whilst COVID is still a threat and how to deal with full storage and prices falling below cash costs for some operators.

Invest in traditional hydrocarbon operational safety/recovery (crisis management and emergency response), because global tolerance for oil spills is constantly reducing. The industry has a lamentable track record of reducing their focus on safety when money is tight, which empirically always leads to more incidents/spills/accidents, greater loss of revenue and reputation and reduced output and income[26].

Thirdly, look to the future;

Innovate wherever possible – LNG as the “transition fuel”[27], hydrogen, ammonia, new plastics, CCUS, digitisation etc.

Look at new supply-chain configuration and new partnerships with customers.

Accelerate technically, especially with AI and advanced analytics.[28]

Both need to happen very fast if the crises which are looming this century are to be mitigated or avoided.

High-quality, coordinated planning at all levels and across multiple sectors offers the best chance of avoiding the visible and predictable crises.

Energy companies need to transform just as fast if they are to stay in business, and support the countries in which they operate.

With sufficient will, success in crisis-avoidance in Africa is possible.

Inverroy have supported national parliaments, renewable energy companies and hydrocarbon energy companies in crisis management, emergency response and horizon-scanning in the UK, Iraq, Mexico, Ghana, Senegal, Niger and Morocco. We also have experience of working in Libya and DRC. We would be delighted to welcome any new clients who might require business continuity and resilience support in today’s rapidly-

As our Sector Lead for Africa, Toby has written a number of blogs focusing on Africa. He has explored issues ranging from water shortages to Higher Education, and the Changing Resilience Picture in Africa.

Inverroy have also worked in Morocco